Noor stands shivering in the cold afternoon light of the courtyard, not from the cold, but from fear.

Dressed in her thick winter coat, she has protested against the men of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), Syria's new de-facto rulers, and the new law in town.

She begins to cry as she explains that three days earlier, just before nine in the evening, armed men had arrived in a black van at her apartment in an upscale neighborhood in the city of Latakia. Together with her children and her husband, an army officer, she was taken out into the street in her pyjamas. The leader of the armed men then moved his own family to her home.

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCNoor - not her real name - is an Alawite, the minority from which the Assad family came, and to which many of the political and military elite of the old regime belonged. Alawites, whose sect is a derivative of Shia Islam, make up about 10% of the population of Syria, which is the majority Sunni. Their heartland is Latakia, on the northwest coast of the Mediterranean in Syria.

As in other cities, several rebel groups have rushed into the power vacuum left after Assad's troops abandoned their positions. The regime had exploited sectarian divisions to seize power, now the Sunni Islamist HTS has pledged to respect all religions in Syria. But the Alawite population of Latakia is afraid.

Some people have not even left their homes since the regime changed because they are worried that there will be a reckoning, and that they will have to pay a huge price for the support of the old regime.

Noor shows CCTV footage from her apartment to 34-year-old Abu Ayoub, HTS's general security chief. In the film, a group of bearded fighters, some wearing baseball caps and others in military fatigues, are pictured on her doorstep.

Quentin Sommerville / BBC

Quentin Sommerville / BBCThey are not from HTS, she says, but another group, rebels from the northern part of the city of Aleppo.

"They broke down the door. There were 10 militants at our door and another 16 waiting down the street with three cars," Noor told Abu Ayoub. Most of his men are from Idlib and Aleppo, where the HTS and allied rebel groups were based before launching the offensive that ousted Assad three weeks ago. They stand around in combat fatigues, holding their rifles and listening intently as she explains how the family's belongings were thrown into the street.

HTS was once aligned with al-Qaeda and is still banned as a terrorist group by most Western countries, although the UK and US say they have been in contact with the group. In a matter of weeks, he has gone from enemy of the state to the law of the land. Abu Ayoub and his men are changing according to the change in roles from revolutionaries to policemen.

Noor is just one of a long line of protesters who have come to their general security station with complaints. The base, the city's former military intelligence headquarters, was perhaps the most feared place in Latakia. Now it's a shambles, with broken radios and equipment scattered across the yard. Shattered photos of Bashar al-Assad lie in the dirt.

A man joins the queue of those who complain. He has a black eye, broken ribs, and his shirt is torn and bloody. He says that men from Idlib had broken into his apartment.

Darren Conway / BBC

Darren Conway / BBC"Some of them were civilians, some of them were wearing military clothes and disguised," he says. "They hit my daughter and aimed weapons at my son's head. They stole money, they stole gold."

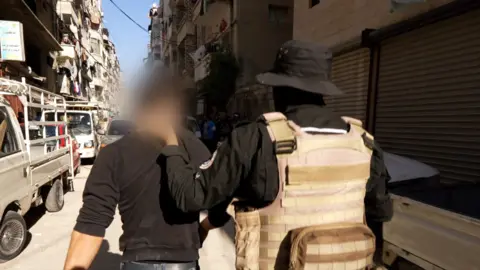

Every call here is a show of force, especially with so many armed groups in the city. With a human being leading them, the HTS security force drives into one of the poorest neighborhoods, weaving through mazes of back streets, old junkyards and middens.

The armed police take up positions on the street and at the door of the apartment. They bring two suspects back to the station for questioning.

But they barely have time to clean their weapons when there is another protest, a dispute over gas bottles that left another man beaten.

He says three men pulled at him.

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCAnother race in the cars to a crowded commercial and residential neighborhood. When the police drag a suspect out into the street - his face still bloody from the earlier fight - local women come to their balconies and shout "Shabiha! Shabiha!". They accuse the suspect of being a member of the militia force, mostly made up of Alawite men, who did the dirty work of the Assad regime.

Since the lightning went to victory over Syria, Islamist HTS has vowed to keep the peace and protect the country's minorities. And every day Abu Ayoub has to make that promise.

"Some infiltrators into the revolution, some saboteurs, and some weak-minded people are taking advantage of the situation in the recently liberated areas," he said. .

Abu Ayoub admits that the situation in the town was "a bit chaotic" but turned his attention to Noor. "We are here now, we were not here when the army left. We were first in Damascus and then we came. They are boys, and we will evict them your house. We will return your things. You have my word," he said. And with that he orders his men into their pick-up trucks and with a siren calls them to go to the apartment.

Latakia is a liberated city. Last Friday, tens of thousands of people from all regions gathered in the streets to celebrate the fall of the Assad dynasty. In a city square, they sat atop the plinth where the statue of Hafez al-Assad, Bashar's father - who ruled for 29 years before his death in 2000 - once stood, and he happily waving the flag of free Syria.

The message of that day was unity, one Syria, without sectarian divisions. But after half a century of tyrannical rule from a regime that fueled sectarian hatred and warned that Alawites would be massacred if they ever lost power, it is a change to say the least. .

On Saturday, three HTS fighters were killed and 14 wounded outside the city, in what they said was a gun battle against a criminal group. HTS, which is trying to keep calm, claims that there was no sectarian element in the attack.

On the way to Noor's apartment, the HTS convoy goes through the streets and passengers cheer them and light the peace sign.

Quentin Sommerville / BBC

Quentin Sommerville / BBCThe new Syrian flag, with its green instead of a red stripe, and three red stars instead of two green, is very common on shop shutters and hanging from balconies. But in Alawite areas, people usually watch in silence as the convoy moves on. Fewer new flags are visible.

Azam al-Ali, 28, an HTS security officer from Deir al-Sour in eastern Syria is sitting in the front seat. After so much oppression, he says, it takes time for people to trust authority again.

"Most of those who are oppressed come with complaints from two groups, the Sunni and the Alawite. We do not differentiate. .

And he notes that Alawites, some of whom were among the poorest in Syria, suffered under Assad's rule.

We arrive at Noor's apartment and half a dozen armed HTS men go up the stairs.

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCThe woman behind the door refuses to open, but after some negotiation the door opens, and she and her family are ordered to leave. Noor goes in to get clothes and books for her daughter who is doing exams. Arms and ammunition belonging to the rebel squatters have been seized.

"When I went to HTS today I was scared," says Noor. "They looked so scary and scary. Honestly, though, they were really nice."

But she does not return to the apartment. One nightmare has ended in Syria, and for Alawites, another has begun, she says.

While packing her things, Noor says that she no longer feels safe in her home.

"It is impossible for me to live here again. I hope, but not soon. At this moment I am not mourning."