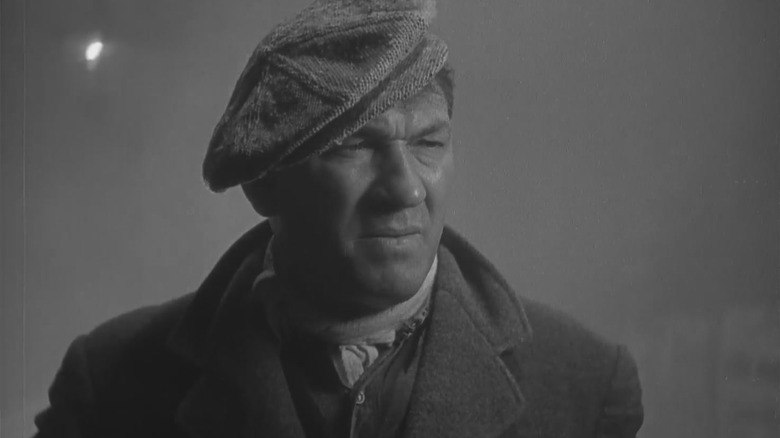

Many Hollywood creatives spend their entire careers trying to win an Oscar, but some of them don't seem to care. Or if they care, some of them have other concerns that take top priority. Such was the case with Dudley Nichols, a screenwriter whose career spanned from Men Without Women in 1930 to Heller in Pink Tights in 1960. In 1936 he won an Academy Award for The Informer, a famous film about an Irish informant wracked with guilt after betraying his friend to the IRA.

Although "The Informer" is not very well known these days, in the decades following its release it was often cited as one of the best films in American cinema. In 2024, however, the film is best known for what happened when its screenwriter won an Oscar. Nichols, who co-founded the Screenwriters Guild, was unhappy with the Academy's refusal to recognize the SWG or support its fight for better pay and proper credit for their work. He boycotted the ceremony, and when the Academy tried to mail him the award, he returned it and wrote an open letter in response:

"As one of the founders of the Screenwriters Guild, which was conceived as a revolt against the Academy and born out of disillusionment with the way it operated against employed talent in any emergency, I deeply regret not being able to accept this award. ", Nichols wrote. "To accept it would be to turn my back on nearly 1,000 members of the Screenwriters Guild."

Dudley Nichols' protests in 1936 were successful

The head of the academy at the time, Frank Capra, he said in response to Nichols' protest, "Membership in the academy has nothing to do with a prize and never has. Dudley Nichols' award will remain, even if he does not accept the statue which is merely a symbol of the award."

Nichols eventually accepted his Oscar in 1938, but only because he had achieved most of his goals for the SGA. Like the Santa Ana Register reported That same year, "The National Labor Relations Board today certified the Screen Writers Guild Inc. as the exclusive bargaining agents for approximately 325 writers employed by 13 Hollywood motion picture studios."

It's not entirely clear how much of an effect Nichols' Oscars boycott had on this score; looking through newspaper archives, not a single reporter seems to have made the connection between the 1936 Nichols boycott and the 1938 SGA revelations. Before and after SWG was certified, it was common for newspapers to mention Nichols' Oscar for The Informer without mentioning his boycott of the award or his reasons for doing so. Even for Nichols' obituary in 1960, newspapers often neglected to mention this detail, although Nichols' refusal to accept the award was undoubtedly one of his weaker moments.

However, Nichols' boycott of the eighth Academy Awards was just one of many moves he made in the fight for better conditions for screenwriters in Hollywood. In the same year that he boycotted the Oscars, the Screen Writers Guild would quickly grow and gain influence, even though so many newspapers were seemingly in the tank for the producers the guild fought against. "The guild of screenwriters is a device of communist radicals", wrote the Washington Herald in April of the same year, "who evidently do not mind slitting their own throats if they can at the same time only succeed in slitting the throats of the manufacturers and the laborers in general." For those who have not forgotten the latest WGA strike since 2023 and the discourse surrounding it, this argument against the writers' union sounds awfully familiar.

Nichols and other guild members continued the fight regardless, and most of the rights they fought for were achieved. including "shorter optional contracts, power to fix loans, (and) deposit for speculative work." This made life easier not only for them, but also for generations of screenwriters who would follow them. On the success of later writers' strikes owes much to the struggles of Nichols' early work.

Dudley Nichols fought for Hollywood unions during a very chaotic time

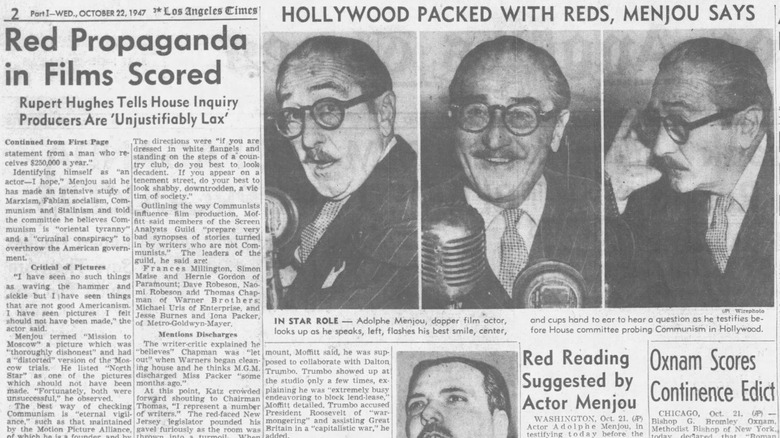

Why were newspapers so hesitant to mention Nichols' Oscars boycott? Perhaps it was because many of them at the time were too busy inciting fear about potential communists in the union Nichols helped found. "Undoubtedly, there are covert communists in the writing business here who would like to enforce the closed shop and, by skillful but recognizable methods, shut off the screen ideas contrary to their own." wrote one columnist in 1938, adding: "Radicals are quite free with their use of words like 'fink', 'scab' and 'house alliance' to those who deviate from their attempts to coerce and terrorize, but any mention of Communism in connection with their activities are condemned as red-baiting take it."

This columnist was Westbrook Pegler, a man who also really hated the New Deal, disapproved of labor unions in general, and opposed anti-lynching laws. Although not particularly revered now, Pegler was at the height of his influence in the 1940s, helping to pave the way for the Second Red Scare that seriously affected the SGA. During the 1940s, the House Un-American Activities Committee investigated countless Hollywood creatives for alleged communist ties. Although the idea of communism infiltrating Hollywood would later be seen as more of a moral panic than a real problem, the damage to the careers of many screenwriters (many of whom were completely blacklisted by Hollywood) could not be returned.

Not even McCarthyism could bring down Dudley Nichols

Dudley Nichols survived the second Red Scare largely unscathed, although as a prominent figure in SWG, his character was still maligned during this period. Writer Rupert Hughes testified that Nichols, whom he described as "certainly very left-wing, though I don't know if he's a Communist," "demanded" Hughes' resignation in 1932 because of Hughes's anti-Communist beliefs.

The charge was never proven; looking through the records, it seems more likely that Hughes and Nichols' disagreement in the early 30s was a result of their differing views on how the SWG should function. "Eha lot a time when we have an olive branch these people see the split hoof,” Nichols said complained in 1938. "They imagineIf every writer is brave enough to stand up for his reasonable rights he must be a radical.”

As the Second Red Scare slowly died down and the writers' union remained intact, Nichols continued to write screenplays and continued to be a respected, award-winning figure in the industry. As the Tulsa World newspaper reports reported in February 1954, "The Screenwriters Guild on Thursday night presented Dudley Nichols with the Laurel Achievement Award, symbolic of the greatest contribution over the years to his craft and guild. Nichols wrote such notable films as Prince Valiant Big Sky, The Bells of St. Mary, For Whom the Bell Tolls, Stagecoach and The Informer. The award was made at the guild's annual dinner and was a decision of its 21 board members."

Source link